The Great Recycling Crash

Recycling is in a crisis – in case you hadn’t noticed. One of the world’s signature pro-environment activities, growing steadily over decades, has crashed. “Is this the End of Recycling?”, asked a headline in The Atlantic last month.

Hundreds of cities across the US and Europe have canceled recycling programs, and/or limited the types of material they accept. Philadelphia is burning about half of its recycling material in an incinerator. Memphis’ international airport sends every collected can, bottle and newspaper from its recycling bins to a landfill. Akron, Ohio, and Arlington, Virginia, are two of many cities that have ended glass recycling. Minneapolis stopped accepting black plastics; Marysville in Michigan will no longer accept eight of 11 categories of items (including glass, newspaper, and mixed paper) for recycling, in order to cut costs; Sacramento halted collection of plastics labeled No. 4 through 7 for several months. Hardest hit have been small town and rural recycling operations. Kingsport, Tennessee, has shut down recycling, Phenix City, Alabama, stopped accepting all plastics, Deltona, Florida, suspended curbside pickup. Residents in smaller towns must now often travel to collection points if they want to recycle. Many more people have become forced to toss plastic and paper into the trash. Incineration is on the rise in Europe. In England, 665,000 more tons of waste were burned at waste-to-energy plants last year than the previous year. And Australia’s recycling industry is facing a crisis as the country struggles to handle the 1.3 million-ton stockpile of recyclable waste it had previously shipped to China.

What’s going on?

The National Sword Policy, that’s what.

China’s National Sword policy, enacted in January 2018, essentially closed the world’s largest market for recycling. China’s recycling processors had handled nearly half of the world’s recyclable waste for the past quarter century. 95% of the plastics collected for recycling in the European Union and 70% in the US were sold and shipped to Chinese processors. 40% of all recyclables in the US headed to China. As reported by Cheryl Katz in Wired, “Everyone was sending their materials to China because their contamination standard was low and their pricing was very competitive,” says Johnny Duong, acting chief operating officer of California Waste Solutions, which handles recycling for Oakland and San Jose. Favorable rates for shipping in cargo vessels that carried Chinese consumer goods abroad and would otherwise return to China empty, coupled with the country’s low labor costs and high demand for recycled materials, made the practice attractive.

The National Sword policy now directs that China will not accept many scrap materials, especially plastics, and others only if they meet a very strict contamination rate of 0.5 percent. In the US contamination rates of recyclables can reach 25%, and had been getting worse – in part due to the growth of recycling itself. China’s action came after many recycling programs had transitioned from requiring consumers to separate paper, plastics, cans, and bottles to today’s more common “single stream,” where it all goes into the same bin. As a result, contamination from food and waste has risen, leaving significant amounts unusable. Since January 2018, China’s plastic imports have plummeted by 99%, touching off the curbside and landfill crisis.

The effects of the policy took some months to become fully visible. Initially, displaced plastics and other materials began to be shipped elsewhere: Thailand, India, Indonesia, Turkey and Vietnam. But their much smaller land areas quickly encountered similar concerns that larger China had encountered, and they have all struggled to deal with the sudden increase in volume and imposed their own restrictions. Now there are no low-income takers for the waste of the US, Europe and Australia. And so more plastics are now ending up in landfills, incinerators, or likely littering the environment as rising costs to haul away recyclable materials increasingly render the practice unprofitable.

Sorting Trash in Vietnam: Photo: NHAC NGUYEN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Look a little farther below the surface, however, and you can find another cause. The American consumer. Not the answer in most press coverage? Let’s look at why China, or really anyplace for that matter, would accept the waste from other countries. As noted earlier in this piece, it’s never really been a great business. Economics have been marginal. What it’s really been about is China’s trade surplus. For decades China has been exporting goods the rest of the world wants, and running up huge surpluses, with consequent political pressure from many places to find something to import in exchange. For a while, the biggest something (after raw materials, of course) was trash. It’s probably no coincidence that the decision to curb these imports comes in a period of declining political relations with the US, especially around the issue of trade. On the other side, American consumers continue to consume more, and discard greater volumes. The cost of finding ways to dispose of America’s trash has been partly subsidized by China’s willingness to take it at low cost. We can see this even more from the fact that even before China’s ban, only 9 percent of discarded plastic in the US was being recycled, while 12 percent was burned. The rest was buried in landfills or simply dumped and left to wash into rivers and oceans.

What’s next? No easy answers, and maybe a silver lining for the waste management industry.

The big impact is on consumers, and it is just beginning to be felt. So far the cost is mostly in terms of environmental concerns, with advocates of more recycling instead seeing a decline. In some cases – particularly in smaller towns and rural areas, cost is appearing in terms of convenience: people are either having to drive farther, and/or having to do more pre-sorting of their disposable items. Over the previous decade, single-stream recycling (where all recyclable items are picked up in an office or at curbside in a single container) went from being used in about 30% of US communities to about 80%; this single stream model provides great convenience for users, but increases both contamination levels and sorting costs. Expect single-stream recycling to drop sharply. Some hard-to-recycle though convenient items are being restricted. In Europe, the European Parliament has banned the use of single-use plastics, such as plastic cutlery; Starbucks has taken a similar approach; plastic shopping bags also face more restrictions.

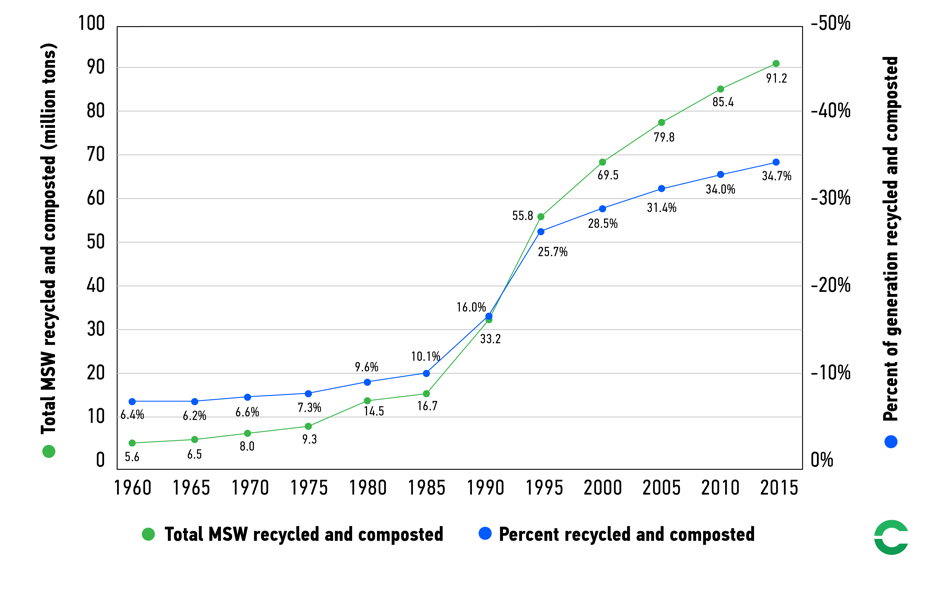

The impact of the great recycling crash is also only beginning to translate into economic costs for consumers. Some of that cost is arriving pre-consumer, as with environmental levies being instituted on plastics in Norway and the UK. More visibly, it is appearing post-consumer, as landfill stations and recycling companies raise their charges to consumers and to municipalities. In places like Berkshire County, in Massachusetts, the municipalities pass those costs onto consumers through higher fees and increased bag prices at transfer stations. This increase in costs is just beginning. The recycling crash is arriving as more waste is being created than ever. According to City Lab (see graphic below), the amount municipal solid waste in the US has grown an astonishing 5-fold since 1985. As Cheryl Katz noted in Wired’s review of recycling, “The United States still has a fair amount of landfill space left, but it’s getting expensive to ship waste hundreds of miles to those landfills. Some of these costs are already being passed on to consumers, but most haven’t—yet.”

Courtesy: City Lab, “China’s National Sword Policy”, Nicole Javorsky

What’s bad news for consumers and cities, having to pay more to manage waste, may be good news – more revenues — for the waste management business. Decades of reliance on China’s de-facto subsidized handling of global waste has meant little money being available for waste management infrastructure in Europe and the US. In general, trash hauling and landfills have been more profitable, and recycling a money losing segment for the same firms. Now more items are going to landfill rather than recycling, which will improve margins for waste managers. Higher recycling fees may help also, although these are offset to a large degree by higher costs. And this increase in revenues means private waste managers are more likely to find the capital needed to build more of the waste management infrastructure needed to address the current crisis.

Some of this new capital investment is becoming visible. Several paper mills in Canada and the US have announced new capacity to process recycled paper. Material recovery facilities are expanding capacity and operations. Some, like Oakland-based California Waste Solutions, are upgrading processes to improve the acceptability of materials to buyers, including in China and other Asian markets. Even some Chinese-based processors, now without raw materials after China’s new standards came into force, are building new plants in the US.

In the longer term, waste management is likely to become a more organized and a more dispersed activity. Instead of most waste going to a single market at de-facto subsidized costs, and sector revenues being insufficient for investment in better sorting, transport, and re-use facilities, we’re likely to see a world closer to equilibrium: revenues in line with the cost of building and operating recycling facilities, and both processors and end-buyers well-spread geographically, with transport costs curbing distances over which waste is transported. It will be more expensive and less convenient for consumers, which in turn may (one crosses one’s fingers) lead to the generation of less waste. It’s a silver lining. Of course right now, it’s a mess.

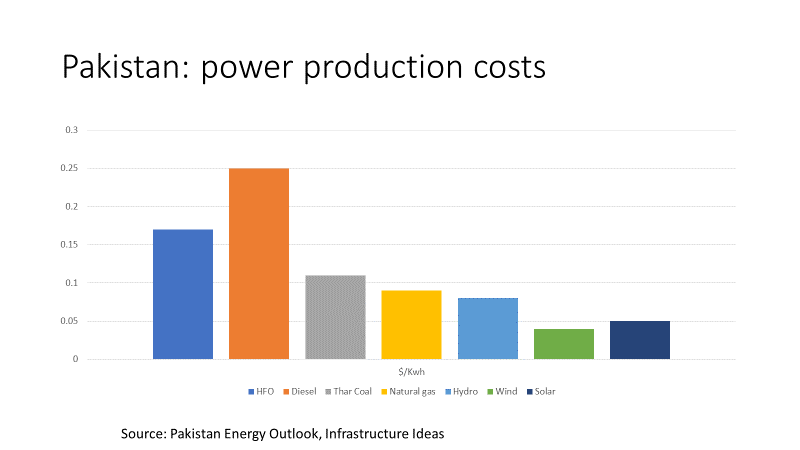

On the one hand, renewable energy is now the cheapest form of electricity generation in Pakistan. This should not be unexpected, given how falling costs have made wind and solar the cheapest options for new capacity in much of the world – accounting for over 50% of all new electricity capacity additions worldwide in 2017 – and Pakistan’s plentiful wind and solar resources. On the other hand, renewable energy proponents carry limited political weight in Pakistan. Proponents of expanded use of coal, by contrast, carry substantial weight – both domestic supporters who would like to see investment in local coal deposits such as the massive Thar field, and external financiers looking to sell coal and coal-fired generation plants – mainly from China. The Chief Minister of Sindh Province, where many of the country’s coal deposits lie, stated in early March that the long-delayed Thar coal-fired plant would “start soon.” Given Pakistan’s long-unstable domestic politics, and perennial foreign-exchange problems, the verdict on the country’s energy transition remains out. The implications are significant – building another 15-20 GW of coal-fired generation in Pakistan in the coming decades could add up to 100 million tons to annual CO2 emissions – an increase of 40% over Pakistan’s current CO2 emissions, and roughly what 25 million cars produce. And, given the contrary trends in prices, probably leave system-wide power costs at least 20% higher than they could be. This is clearly a country whose energy politics bear watching.

On the one hand, renewable energy is now the cheapest form of electricity generation in Pakistan. This should not be unexpected, given how falling costs have made wind and solar the cheapest options for new capacity in much of the world – accounting for over 50% of all new electricity capacity additions worldwide in 2017 – and Pakistan’s plentiful wind and solar resources. On the other hand, renewable energy proponents carry limited political weight in Pakistan. Proponents of expanded use of coal, by contrast, carry substantial weight – both domestic supporters who would like to see investment in local coal deposits such as the massive Thar field, and external financiers looking to sell coal and coal-fired generation plants – mainly from China. The Chief Minister of Sindh Province, where many of the country’s coal deposits lie, stated in early March that the long-delayed Thar coal-fired plant would “start soon.” Given Pakistan’s long-unstable domestic politics, and perennial foreign-exchange problems, the verdict on the country’s energy transition remains out. The implications are significant – building another 15-20 GW of coal-fired generation in Pakistan in the coming decades could add up to 100 million tons to annual CO2 emissions – an increase of 40% over Pakistan’s current CO2 emissions, and roughly what 25 million cars produce. And, given the contrary trends in prices, probably leave system-wide power costs at least 20% higher than they could be. This is clearly a country whose energy politics bear watching.