The Coming Decommissioning Wave

October 2019

Our previous Infrastructure Ideas column (What Next for Coal?) outlined the (declining) state of the coal-fired electricity generation business. Driven until now by the age of plants and weakening economics, this decline is about to be sharply accelerated by climate concerns. An important consequence of this acceleration will be the impact and costs of decommissioning old – and not so old – generation facilities. The funds required for this decommissioning will be in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Decommissioning, in fact, will likely become one of the largest areas of infrastructure-related financing in the coming decades! Why is this going to happen, and how will it work? Read on…

Power plants close all the time. Since 2000, over 3,000 generating units have closed just in the United States. Historically these closures have been primarily end-of-technical-life retirements, with the post WWII building boom and average expected plant life of around 40 years. More are scheduled to close in coming years: another 6,000 plants in the US have been in production over 40 years, representing about 1/3 of national generating capacity.

What has begun to change is the rationale for closing generating plants. Already, economics – as opposed to just end-of-technical-life – has become a major factor in closing facilities. This is a predictable outcome of a sector which has gone from essentially stable to highly dynamic – driven by technology change (see Not Your Father’s Infrastructure). As prices of electricity from newly-built plants continue to plummet, the higher costs of power from older generating plants are becoming much more visible and problematic for buyers and policy-makers.

The first group of generating facilities to feel this economic pressure has been, interestingly, wind farms. The early generation of wind farms, often built to meet local environmental concerns and with output priced at a premium in most electricity markets, are now vastly more expensive than the newly-built wind farms (or solar). As they come to the end of their initial sales contracts, keeping these wind farms in service is economically unattractive. The first of these farms were coming on stream in the late 1990s, often with 15- or 20-years Power Purchase Agreements and typically being paid on the basis of pre-set Feed-in-Tariffs; they are now coming to the end of those contracts. 2015 was the first year that saw considerable wind farm retirements in the US, with an average plant life of 15 – as opposed to 40 – years. Germany, a country which was an early leader in pushing a “green energy” agenda, has a large-scale version of this issue. 20-year FITs will expire beginning in 2020 for over 20,000 onshore wind turbines, with a collective capacity of 2.4 gigawatts. Owners face decisions of whether to retire the wind farms or repower them (another potential option involves corporate PPAs, along the lines of the recent contract signed between Statkraft and Daimler, whereby Daimler will buy – for a 3 to 5-year period – power from wind farms whose guaranteed FIT contracts are expiring). Elsewhere, repowering of wind turbines has become a major business. Repowering began as replacement of old turbines with taller, and more efficient machines on existing sites; today operators switch even newer machines for larger and upgraded turbines or replacing other components. This makes sense where acquisition of land for new sites may be difficult, and where revenues are contingent on being able to compete with new lower-cost alternatives. In 2018 over a gigawatt of wind capacity was repowered in the US, and an estimated half gigawatt was repowered in Europe. The economic pressure to replace early-generation and more expensive renewables with new and cheaper plants extends well beyond Western Europe and 20-year old wind farms. FITs, the preferred first generation of purchase contracts for wind farms and some solar, have come to be seen as highly unfavorable to buyers, as costs of new equipment kept falling. Spain in the early 2010s, Portugal and several Eastern European countries either forced retroactive changes to purchase contracts or terminated them prematurely, trying to reduce the fiscal costs of expensive early renewable contracts. Yet even with competitive auctions replacing FITs, there remain economically-based risks to contracts. In India, the new state government in Andhra Pradesh has sought to terminate purchase contracts for solar power which are less than five years old. As prices for new solar and wind capacity, and for associated storage, continue to fall, this pressure will be more widespread.

The bigger losers from the economic pressure to switch power supplies, however, are clearly producers of thermal power. In the few places which still reply on oil to fire generation plants, the cost differential between existing supply and new alternatives is massive. In Kenya, the Government has announced its intention to shut several expensive oil-fired plants, starting with long-established and pioneering IPPs such as Iberafrica, Tsavo and Kipevu-diesel. With Senegal and other relatively small markets demonstrating that the option of below 5 cent/kilowatt-hour solar is a reality practically everywhere, we should expect a wave of closures of older oil-fired plants – whose costs run upwards of 15 cents/KwH. Globally, though, oil-fired plants make up a tiny part of electricity capacity. The biggest losers are rather in coal.

Many coal-fired plants have been closing for end-of-life technical reasons. From 2000 to 2015, over 50 gigawatts of coal-fired capacity was closed just in the US, with average closed plant life of over 50 years. More recently, coal – long seen as the cheapest form of electricity supply – has also begun to be supplanted on economic grounds. In the US natural gas-fired plants have come to be widely preferred. Endesa, in Spain, announced two weeks ago that it would shut down 7.5 gigawatts of coal power; the main reason cited was declining competitiveness, noting that its sales of coal power had declined 50% in the previous year. These are large amounts: Endesa has flagged a write-down of over $1 billion related to the retirements. Yet these amounts are still ripples compared with the coming wave.

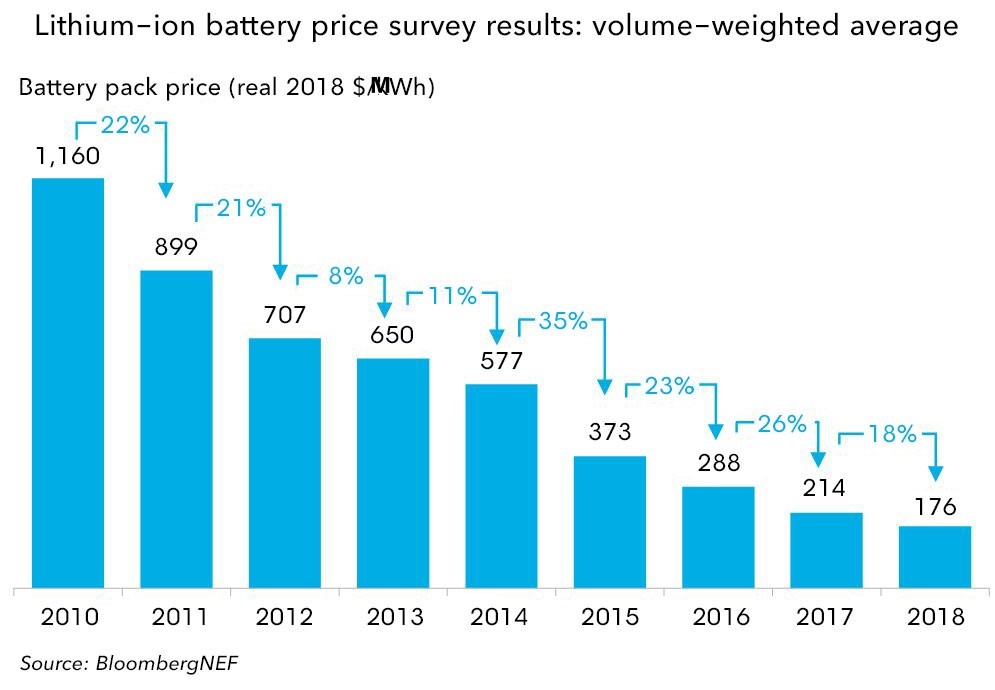

What will drive a major acceleration of coal-fired plant closures is the continued worsening of economics, and a third factor, coming on top of technical retirements and economic pressures. This third factor is climate concerns. On economics, as discussed in our previous post, various analyses in the US show that costs of electricity could be reduced by closing between 1/3 and 2/3 of the existing coal fleet today, with that share rising to 85% by 2025 and 96% (about 250 gigawatts) by 2030. Regardless of how precisely accurate these estimates are, it is fairly clear that an amount of coal-fired capacity far larger than that retired since 2000 is or is about to become uneconomic compared to alternatives. Coal is not getting cheaper, but wind and solar, and storage, continue to get much cheaper. The big killer, though, we expect will be climate concerns.

The latest IPCC report, along with several others issued in conjunction with last month’s Climate Week, is fueling more concerns about the pace and likely extent of climate change. New data on the pace of climate change and GHG emissions levels is alarming. Every new analysis shows climate change is proceeding faster than previously expected, and pathways to lower-impact carbon concentration and temperature change require larger shifts than in previous analyses. The International Energy Association’s latest annual review found that as a result of higher energy consumption, 2018 global energy-related CO2 emissions increased to 33.1 Gigatons of CO2, rather than decreasing as they had from 2014 to 2016. The IEA also found that climate change is already causing a negative feedback loop in emissions: they estimated that weather conditions were responsible for almost 1/5th of the increase in global energy demand, as average winter and summer temperatures in some regions approached or exceeded historical records – driving up demand for heating and cooling alike, while lower-carbon options did not scale fast enough to meet the rise in demand. Another report coordinated by the World Meteorological Organization, says current plans would lead to a rise in average global temperatures of between 2.9C and 3.4C by 2100, more than double the level targeted in the Paris agreements. The trend seems clear, and before long public concerns will drive much more aggressive public policies.

Coal-fired power generation continues to be the single largest emitter, accounting for 30% of all energy-related carbon dioxide emissions. In all analyses, phasing out coal from the electricity sector is the single most important step to get in line with 1.5°C, and recommendations are getting steadily more strident and draconian. Canceling potential new coal plants will clearly not be enough. Another report from last month, this one by Climate Analytics states that although the new coal pipeline shrunk by 75% since the adoption of the Paris Agreement, to get on a 1.5°C pathway will require shutting down coal plants before the end of their technical lifetime. The report’s models show a need to go from current global coal-fired generation of 9,200 Terrawatt-hours all the way down to 2,000 TWH by 2030 – equivalent to decommissioning about 1.6 Terrawatts (1,600 Gigawatts) of generation capacity. Still another report modeled the need for emissions from coal power to peak in 2020 and fall to zero by 2040 if the world is to meet the Paris goals. Shutting down so much coal-fired generation capacity is a tall order. Yet the political pressure in this direction is building. Several countries in Europe have announced coal phase-out plans: France for 2022; Italy, the U.K. and Ireland for 2025; Denmark, Spain, the Netherlands, Portugal and Finland for 2030, and Germany for 2038. Even coal-rich South Africa is studying a plan involving substantial closures.

This potential decommissioning wave would be very expensive. Closing a coal-fired plant is a high cost exercise. The write-down associated with Endesa’s closures in Spain, noted above, comes to about $200/ KW of capacity. Resources for the Future in 2017 issued a detailed analysis of decommissioning costs for power stations in the US, coming up with a range of observed costs for coal of $21 to $460/KW of capacity, and a mean cost of $117, and estimated future decommissioning costs of between $50-150/ KW. These estimates are slightly lower than the costs indicated by Endesa, but are in the same ballpark, and we can get a rough idea of aggregate costs by applying a midpoint (say $100/KW) to the global coal fleet. This gives us the following projections:

• For retiring 250 gigawatt of coal generation capacity in the US, an implied a cost of $25 billion.

• For retiring 1,600 gigawatt of coal generation capacity around the world, an implied cost of $160 billion.

These costs are large… but are only a part of the picture. The analysis here includes the engineering specific costs, essentially technical and environmental costs associated with shutting down a plant, and cleaning up its site. It does not include other important costs associated with decommissioning, namely labor force and community adjustment costs, and – most critically for newer facilities – foregone revenue and breakage costs. For worker retraining and support, and adjustment funding for affected communities and regions, there are no clear estimates available. Germany’s decommissioning roadmap calls for about $40B in support to affected regions over 20 years, so we can see that the numbers – assuming governments aim to help – are not small. That $40B is greater than the estimated technical costs of retiring the entire US coal fleet. For a ballpark estimate, we could then say:

• For retiring 1,600 gigawatt of coal generation capacity around the world, an implied cost – including community/regional adjustment support — of $300 billion or more.

This still leaves the cost of foregone revenues for those who built and own the plants. In markets where many of the plants are approaching technical end-of-life, these costs may be low. Same in merchant markets where coal is losing customers on the basis of economics, and renewables and/or gas-fired plants are reaching significant scale. But in Asia, where the average age of the coal-fired fleet is closer to 10 years rather than 40, this is going to be a significant factor. If one assumes each megawatt of coal generation capacity has cost about $1M, and has associated equity of around $250,000 and debt of around $750,000, we can do a back-of-the envelope estimate of breakage costs for some 800 GW of “younger” Asian coal plants:

• At an annual rate of return target of 7.5%, with 30 years yet to go, potential future flows to equity over 30 more years would amount to about… $500 billion.

• Assuming average initial debt maturities of about 15 years, so that 2/3 of debt would already be repaid, this would leave outstanding principal debt in the range of … $200 billion

Obviously there are multiple assumptions embedded throughout these estimates. What they serve to show, however, is that the costs associated decommissioning the existing global coal fleet over the next two decades – assuming public opinion and politics coalesce around the issue, which we expect to happen – are very high. As in close to $1 trillion. Not to mention another trillion or so to build substitute renewable energy generation capacity. Annual investment today for comparison, around the world, in renewable energy? Less than $300 billion.

There are a few ideas already, at a local level, about how decommissioning costs might be funded. Germany’s roadmap includes reverse auctions for closure subsidies, where those bidding for the lowest amount of support would get funding. Eventually, plants not winning support at these auctions would be forced to close without state subsidies. Costs of legal challenges have not yet been considered. South Africa’s potential roadmap envisages donor and financial institution support to create a fund, managed by Eskom, to finance adjustment in coal-heavy parts of the country, support workers, and help balance Eskom’s finances during the transition away from coal. Colorado has a plan whereby securitization from ratepayer-backed bonds would pay out plants, and some of the bond income would go for helping workers in affected areas.

However these ideas play out, one thing is highly likely: decommissioning coal-fired plants will become a massive competitor for infrastructure-related financing in the coming two decades. The public portion of these costs – whether through a Global Fund, country-or regional specific vehicles, or just government spending – are very likely to exceed cumulative subsidies offered to renewable energy projects in their early years. A lot of funding, and a lot of creativity, will be absorbed here.