Asia’s Energy Transition: Pakistan

This is the first of a series on the energy transition in Asia’s largest economies. Asia is the most important global market for energy consumption, investment, and greenhouse-gas emissions. Asia is also a region in the midst of a large-scale energy transition, whose pattern and evolution remains to be determined. How this energy transition evolves has more importance to the future of climate change, and to the future of energy investments, than that of any other region. Infrastructure Ideas will focus in turn on the state-of-play in this transition in several of Asia’s big economies, starting with Pakistan.

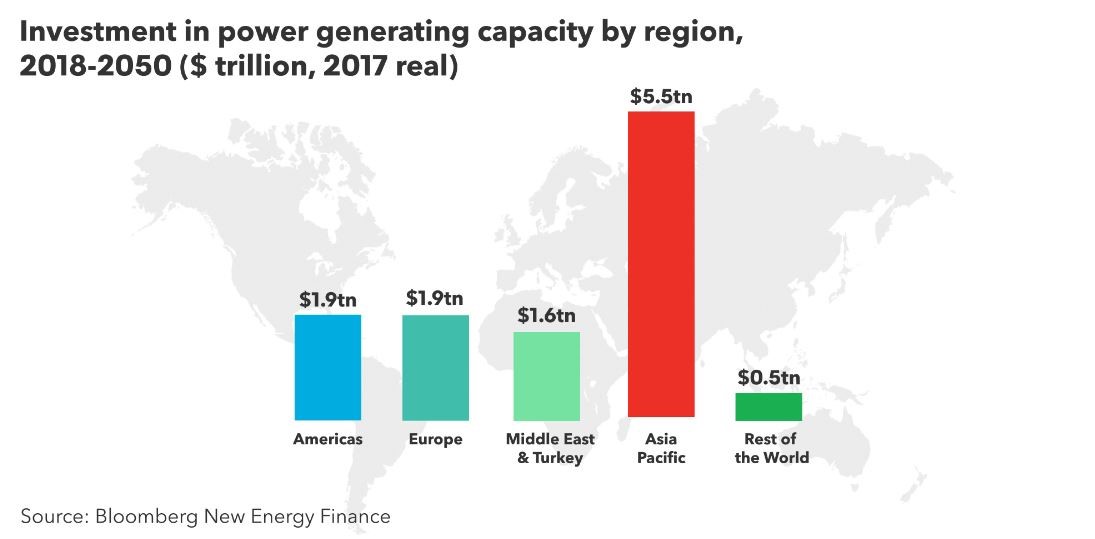

A few numbers illustrate the importance of Asia in the energy world. Between economic growth and connecting the underserved (just under 500 million of the 1 million people without access to reliable electricity are in Asia), the region dwarfs all others in expected energy consumption growth. Bloomberg New Energy Finance projects that, in Asia, over $5 trillion will be invested in power generation capacity from now to 2050, over $180 billion per annum. Asia is expected to account for nearly 50% of all such investment globally.

Asia-Pacific also accounts now for about half of all Greenhouse Gas emissions, and in line with growing energy consumption, the growth rate of emissions from Asia, at over 3% p.a., is triple the growth rate of emissions of the rest of the world. Behind this high share of GHG emissions is not only overall energy consumption growth, but more importantly how much of electricity production in Asia is coal-fired. 67% of all coal-fired generation capacity is in Asia, and essentially all of the growth in new coal-fired capacity globally is in Asia. So as well-reported, Asia is the key battleground for future GHG emissions evolution, and for the scope of future climate change. How decisions are made about more coal, less coal, and the speed of adoption of renewable energy sources will have a disproportionate effect on the rest of the world and future generations.

Pakistan is a key player in Asia’s energy transition, albeit one drawing far less attention than China and India. This is somewhat surprising, given that Pakistan is the world’s 6th most populous country, with about 200 million people. Pakistan also has plans for larger investment levels in new power capacity than all but a handful of countries, and some plans to increase coal-fired electricity production by over 500%… so an important country on many fronts! Let’s look more closely at the state of play.

For a country with as many people as Pakistan, and which has recorded solid economic growth for decades, power production is remarkably low. Total generation capacity today in the country is only just over 25 Gigawatts (GWs), and per capita electricity consumption is only 2/3 of that in India, and only 1/3 of that in Egypt. While 90 million people have gained access to formal electricity over the last two decades, there are still some 50 million people without access, and industry is hampered by extensive load-shedding, often over 10 hours a day. Thus increasing power availability has been a high government priority in Pakistan for a long time, and one can expect that the country will add substantial new production capacity over the next couple of decades.

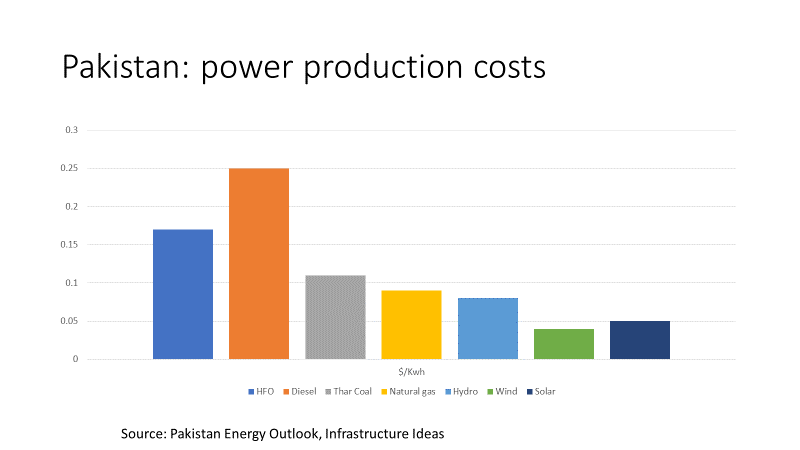

Pakistan’s power sector is of high importance – for provision of basic services, supporting economic and job growth, and for public finances. It also has some oddities. One is the unusually high share of oil-fired generation: about 1/3 of Pakistan’s electricity is produced from either diesel or fuel oil, probably the highest ratio – by far – of any of the world’s largest countries. This has had and continues to have major negative consequences in terms of higher costs, high GHG and particulate emissions, and large trade deficits (Pakistan imports most of its oil). Hydropower and natural gas-fired generation each account for just under 30% of production, coal about 5% and nuclear a little less. Another oddity (shared with a small handful of its Asian neighbors) is the high percentage of power production which is government-run, at about 50%. A 2018 World Bank Report (“In the Dark”, World Bank 2018) estimated that these public sector plants use 17-28% more fuel per output than their private sector counterparts, and that mostly public policy and management inefficiencies in electricity cost the country 6.5% of GDP annually.

In the last five years, Pakistan has entered into a new energy transition, whose direction and outcomes remain very uncertain. The key energy policy decisions going forward for Pakistan revolve around its current transition, and the 20-30 GW of new electricity production capacity it seeks to add.

It has been clear to the Government that continued reliance on oil-fired generation is financially impossible. Yet between the choices of coal, gas, hydropower, wind and solar, the right direction has not been obvious. Development of more coal-fired capacity has had many supporters in Pakistan: the country has large domestic coal resources, coal has historically been a cheap source of fuel, and some government plans have called for coal to assume an up to 30% share of electricity production – compared to about 5% today. Domestic natural gas became important in the decades after independence, but domestic fields are essentially exhausted, and new imports of gas – while important – are at best replacing previous domestic sources, and are in part diverted to domestic fertilizer production. So the share of gas-fired power production is likely to decline substantially. Hydropower may be an important part of the solution. Pakistan has important developed and undeveloped hydropower potential. In the early decades after independence, large-scale dams were constructed by the country’s public sector utility: its chronic losses and mismanagement have essentially made further investment out of the question. Pakistan has instead turned to auctions, whose winners have to date been dominated by Chinese firms, notably China Three Gorges. This holds some promise of relatively low cost and low emission capacity growth, but contentious water ownership issues close to the border with India, climate-change related hydrological uncertainties, and the sheer scale of the new plants likely limit how big a role they play in overall country capacity growth. This leaves the key uncertainties of the transition between large-scale coal-fired generation increases, and accelerated development of wind and solar resources.

While not an early adopter, Pakistan has begun to replicate the renewable energy auction procurement mechanisms which have so strongly impacted many emerging markets. Roughly 40 new wind and solar farms have been provided PPAs, and at prices (US$0.05-0.07) well below Pakistan’s average power costs.

On the one hand, renewable energy is now the cheapest form of electricity generation in Pakistan. This should not be unexpected, given how falling costs have made wind and solar the cheapest options for new capacity in much of the world – accounting for over 50% of all new electricity capacity additions worldwide in 2017 – and Pakistan’s plentiful wind and solar resources. On the other hand, renewable energy proponents carry limited political weight in Pakistan. Proponents of expanded use of coal, by contrast, carry substantial weight – both domestic supporters who would like to see investment in local coal deposits such as the massive Thar field, and external financiers looking to sell coal and coal-fired generation plants – mainly from China. The Chief Minister of Sindh Province, where many of the country’s coal deposits lie, stated in early March that the long-delayed Thar coal-fired plant would “start soon.” Given Pakistan’s long-unstable domestic politics, and perennial foreign-exchange problems, the verdict on the country’s energy transition remains out. The implications are significant – building another 15-20 GW of coal-fired generation in Pakistan in the coming decades could add up to 100 million tons to annual CO2 emissions – an increase of 40% over Pakistan’s current CO2 emissions, and roughly what 25 million cars produce. And, given the contrary trends in prices, probably leave system-wide power costs at least 20% higher than they could be. This is clearly a country whose energy politics bear watching.

On the one hand, renewable energy is now the cheapest form of electricity generation in Pakistan. This should not be unexpected, given how falling costs have made wind and solar the cheapest options for new capacity in much of the world – accounting for over 50% of all new electricity capacity additions worldwide in 2017 – and Pakistan’s plentiful wind and solar resources. On the other hand, renewable energy proponents carry limited political weight in Pakistan. Proponents of expanded use of coal, by contrast, carry substantial weight – both domestic supporters who would like to see investment in local coal deposits such as the massive Thar field, and external financiers looking to sell coal and coal-fired generation plants – mainly from China. The Chief Minister of Sindh Province, where many of the country’s coal deposits lie, stated in early March that the long-delayed Thar coal-fired plant would “start soon.” Given Pakistan’s long-unstable domestic politics, and perennial foreign-exchange problems, the verdict on the country’s energy transition remains out. The implications are significant – building another 15-20 GW of coal-fired generation in Pakistan in the coming decades could add up to 100 million tons to annual CO2 emissions – an increase of 40% over Pakistan’s current CO2 emissions, and roughly what 25 million cars produce. And, given the contrary trends in prices, probably leave system-wide power costs at least 20% higher than they could be. This is clearly a country whose energy politics bear watching.

Some positive signs? In January, the 1,320 MW, the proposed Rahim Yar Khan imported coal-fired power plant was shelved, reportedly over concerns about increased fossil fuel imports. And in February, during a State visit, Saudi Arabia’s ACWA power, one of the largest wind and solar generation companies globally, was quoted as seeing the potential for up to $4 billion in investment in renewables in Pakistan.